The launch was originally scheduled for Thursday, but NASA was forced to stand down because of Hurricane Milton, which made landfall late Wednesday along Florida’s west coast, near Siesta Key. Kennedy Space Center was closed as the storm tore across the state, lashing much of the Florida Peninsula with powerful winds and heavy rain.

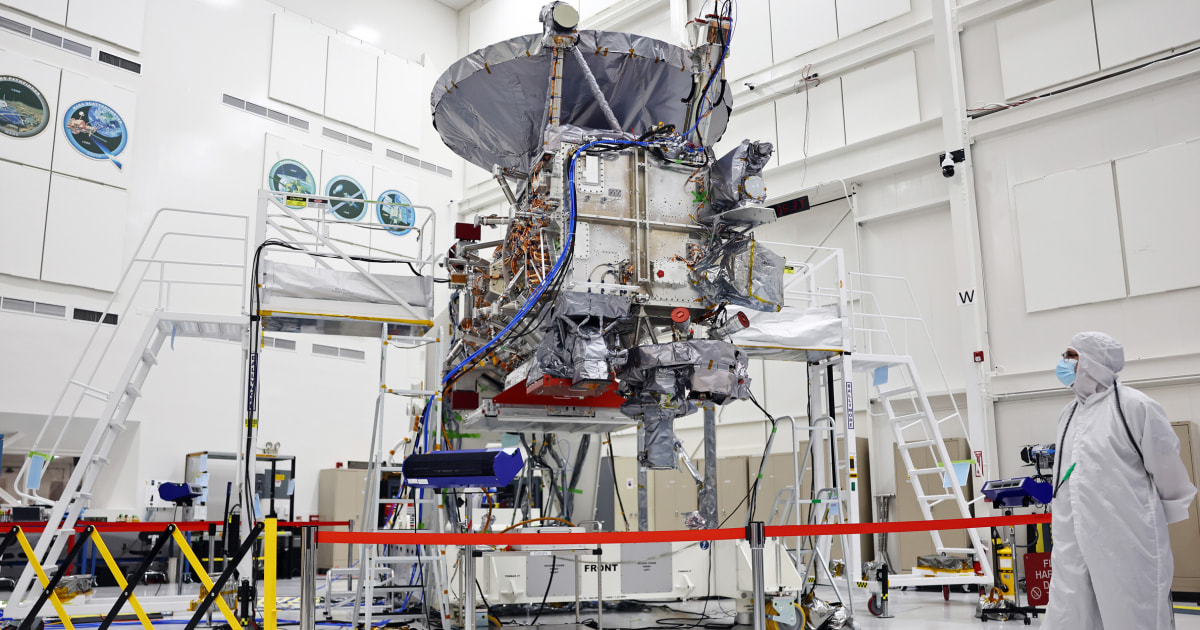

The delay was a minor setback in a mission that has taken more than a decade of planning and development.

“It feels surreal,” said Jordan Evans, the mission’s project manager at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. “There have been battles at every level, from early on with the initial concept for the mission, through getting approved, through each milestone and overcoming various problems along the way. To be at this point, watching the team get ready, is incredible.”

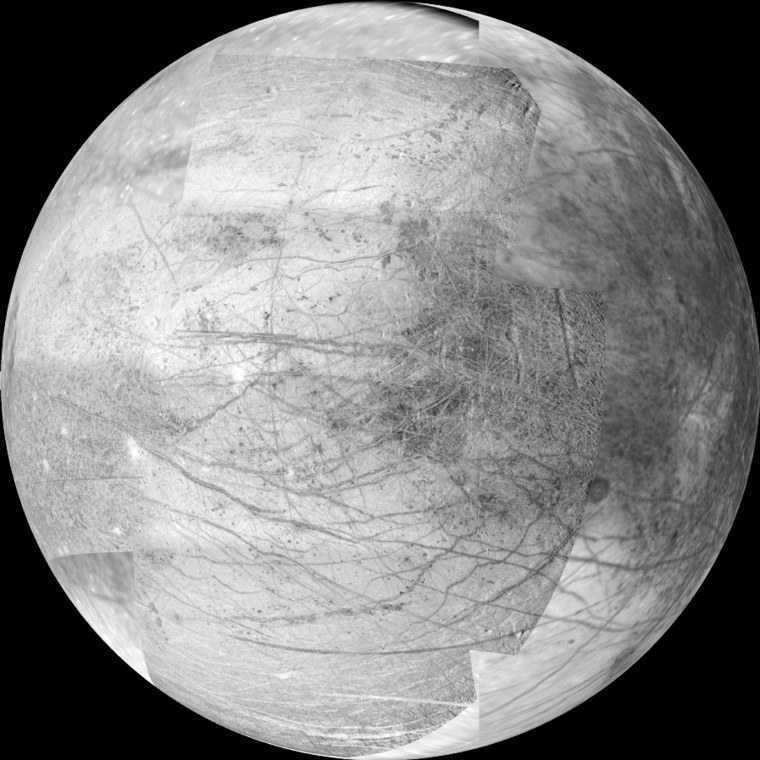

Europa Clipper is not embarking on a life-detection mission. Rather, it will study the composition of the ice-encased moon, along with its internal structure and geology. That information could help scientists confirm whether Europa has the right ingredients to support life now — or whether it did at some point.

“We are looking for a habitable environment,” said Bonnie Buratti, the mission’s deputy project scientist at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. “We’re trying to look for the necessities for life, which are liquid water — and we’re pretty sure that’s there — the right chemistry and energy, whether from active geology or something else, that acts almost like a battery to push life along.”

Buratti said there is strong scientific evidence that a vast ocean lurks beneath the moon’s icy surface. Europa’s internal ocean, in fact, is estimated to have twice the volume of all of Earth’s oceans combined, according to NASA.

Europa Clipper is scheduled to enter Jupiter’s orbit in 2030 after a six-year journey of 1.8 billion miles.

It will give researchers new insights via 49 close flybys of the moon over four years.

“We’ll definitely get the thickness of the ice crust and whether there are little ponds in there,” Buratti said. “With the ocean, I think we’ll eventually understand how deep it is.”

To make those observations, the spacecraft will fly through harsh radiation environments generated by Jupiter’s enormous magnetic field, which NASA says is around 20,000 times stronger than Earth’s.

“If we were to just go into orbit around Europa and study it, the radiation would likely kill off even the most radiation-hardened electronics within one to two months,” Evans said.

Instead, mission managers developed a way for the probe to orbit Jupiter in harmony with the icy moon — a kind of cosmic duet that will help preserve its instruments from prolonged exposure to punishing radiation.

“So, every six times that Europa goes around Jupiter, or every 21 days, we’ll be in the exact spot in the universe to be right next to Europa,” Evans said. “And every flyby will be different, so we can get near global coverage of the moon.”

But the team will need to exercise patience. Before it reaches Jupiter, the spacecraft will first pass Mars and then swing around Earth again, using both planets’ gravity to slingshot it deeper into space.

Europa was discovered in 1610 by the Italian astronomer Galileo Galilei. The icy body is the fourth-largest of Jupiter’s 95 known moons.

Several space probes have made observations of Europa before — including NASA’s Voyager 1, Voyager 2 and Galileo missions — but this will be the first dedicated mission to the moon and NASA’s first time studying an ocean world beyond Earth.

That milestone has been a long time coming for Buratti, who wrote her thesis on Europa as a graduate student at Cornell University in the 1980s.

“I’ve only actually been on this mission for 2½ years. I didn’t start on it,” she said. “But I’m just overjoyed to get to come back to something that is so near and dear to my heart. It really is a dream.”