A theater legend, a superstar baseball player and a trailblazing judge were among the notable Americans of Latino heritage who died in 2024. As we do each year, we look back at their unique achievements and the paths they carved.

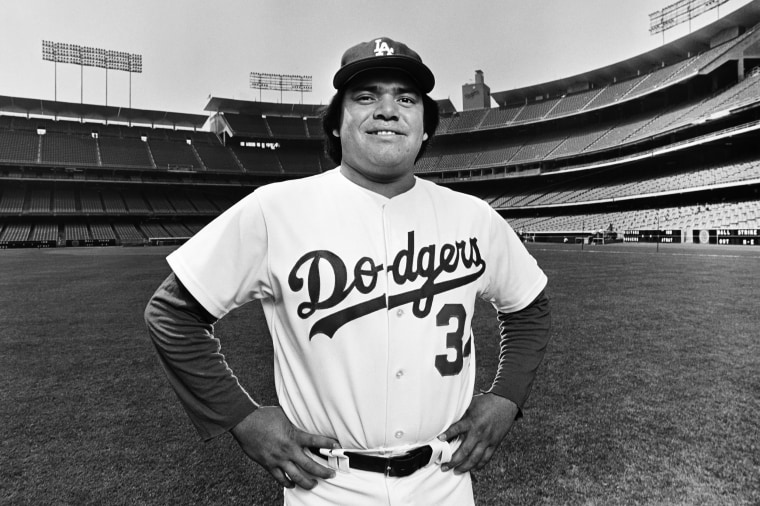

FERNANDO VALENZUELA, 63, baseball star. He came from a small village in Mexico. He was a bit chubby. His English was limited. And by age 20, he’d touched off a fan frenzy pitching for the Los Angeles Dodgers.

In his first season, Valenzuela won the 1981 National League Cy Young Award and the Rookie of the Year Award — and helped the Dodgers win the World Series. When he made the cover of Sports Illustrated, the headline read: “UNREAL!”

As Valenzuela rose to stardom, “Fernando-mania” swept Los Angeles. His performances on the mound were likened to “a religious experience.” His pitching spiked attendance at Dodgers games. In 1986, Valenzuela became the highest-paid pitcher in baseball with a deal that included a one-year salary of over $2 million.

Many Latinos were drawn to the unassuming player with a distinctive windup pitch. “Fernando ended up in L.A., which is like the Mexican capital of the U.S., at just the right time,” Los Angeles Times columnist Gustavo Arellano said. “He awakened a new fan base. People were thirsting for a Latino ballplayer, and the Dodgers, up to that point, had never had a superstar Latino player.”

Valenzuela’s heyday in the 1980s came as the country was debating immigration reform and the Latino population was rising. His success helped heal old wounds in Los Angeles’ Mexican American community over the displacement of families before the building of Dodger Stadium.

In 17 major-league seasons, Valenzuela played for six teams and was a six-time All-Star. Last year, the Dodgers retired his jersey in his honor.

“He was our hero. Even after he retired, he was still ‘El Toro’ (The Bull),” Arellano said. “He transcended sports, and that’s why people will remember him and continue to respect him. He was the best of the best.”

CHITA RIVERA, 91, legendary Broadway actor and singer. Rivera is best known for her breakout role as Anita in the original 1957 stage production of “West Side Story.” Of Puerto Rican heritage, she appeared in 18 Broadway shows across seven decades, including lead roles in “Bye Bye Birdie” and “Chicago.”

A 10-time Tony Award nominee, Rivera won Tony Awards for “The Rink” and “Kiss of the Spider Woman.” She received a Lifetime Achievement Tony in 2018.

Broadway choreographer Sergio Trujillo first met Rivera at a rehearsal for “Kiss of the Spider Woman.” “We [dancers] all got very nervous doing a number in front of her. She seemed so vibrant and full of life,” he said. “At the end, she gave us a standing ovation. Our eyes just locked, and that was the beginning of an over 30-year friendship.”

“She was an incredibly warm person, very fun and cuddly, with a sharp sense of humor,” Trujillo said, adding that he and Rivera loved playing pranks on each other. “One time, on tour, I popped out of a car trunk to scare her, and she screamed and then chased me down the street!”

Rivera’s home was on the stage, Trujillo said. “She always kept going with her artistry. She knew what her gift was and what her destiny was meant to be.”

In 2002, Rivera was the first Latina to receive the Kennedy Center Honor. In 2009, she was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

“Chita was one of those people who had a very big heart,” Broadway veteran Priscilla Lopez said. “She had an incredible work ethic. She never missed a show. Never.”

“In our community, everybody worked with Chita or knew her,” Lopez said. And everybody loved her.”

RICARDO M. URBINA, 78, federal judge. Of Honduran and Puerto Rican heritage, Urbina was a high school and Georgetown University track star. But in 1967 he was denied admittance to the New York Athletic Club, then the top training facility for American Olympians. His rejection led to widespread protests by athletes against discrimination, culminating with African American athletes’ raising their fists on the podium at the 1968 Mexico City Summer Olympics.

After having missed qualifying for the Olympics by less than a second, Urbina graduated from Georgetown Law. In 1981, he was the first Latino to be appointed as a Superior Court judge in Washington D.C., and in 1994, he became the first Latino appointed to the U.S. District Court in Washington, D.C. He worked on major cases involving gun rights, terrorism and civil liberties. In 2012, he retired after over 30 years on the bench.

“Every Latino you see on the bench in D.C., he helped us,” said Kenia Seoane López, an associate judge on the D.C. Superior Court. “He provided us with moral support, process support and led the way for many of us.”

“Judge Urbina leaves behind an army of people whose achievements he helped craft,” López said, “His legacy is decades of mentoring Latinos in the legal field.”

OZZIE VIRGIL SR., 92, baseball pioneer. In 1956, Virgil made history when he took the field for the New York Giants as the first Dominican-born player in Major League Baseball. Virgil paved the way for Dominicans and other Latinos in baseball. Today, more MLB players come from the Dominican Republic than from anywhere else besides the U.S.

In 1958, Virgil was the first Black player to play for the Detroit Tigers, before he went on to play for the Baltimore Orioles and the Pittsburgh Pirates. After he retired as a player in 1969, he was an MLB coach for 19 seasons and a manager in Latin America.

“He swung his way off the island,” said Ozzie Virgil Jr., himself a former MLB player. Despite the racism Virgil experienced early in his career, his son said, he “was proud of leading the way for Latino and Black players.”

“He was the first,” Virgil Jr. said, “and he was proud that no one could ever take that record from him.”

DOLORES MADRIGAL, 90, plaintiff in landmark sterilization case. In 1973, Madrigal was in labor with her second child at Los Angeles County-USC Medical Center. Scared and in pain, she signed a paper that nurses thrust upon her. Only later did Madrigal learn that she had consented to be sterilized. Her dreams of having a large family were destroyed.

In 1975, Madrigal was the lead plaintiff in a class-action lawsuit against the hospital. It alleged that she and other Mexican American women had been sterilized in violation of their civil rights.

While the lawsuit was unsuccessful, it changed the medical profession’s attitudes toward working-class communities. Los Angeles hospitals began to offer bilingual sterilization information and to hire more bilingual staff members. In 2018, the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors apologized to women who had undergone coerced sterilizations from 1968 to 1974.

“It’s considered a landmark case because of the issues: the right to bodily autonomy, the right to have children,” said Virginia Espino, a co-producer of the documentary “No Más Bebés” (“No More Babies”). “It was an argument against the policing of our bodies and for the validation of Mexican motherhood. Even though they lost the lawsuit, it was important to put that argument on record.”

JOHNNY CANALES, 77, TV host and impresario. In 1983, Canales, an Army veteran and former DJ, began hosting “The Johnny Canales Show” in Corpus Christi, Texas. His bilingual variety show was subsequently picked up by Univision and Telemundo and seen throughout the Americas. Canales, who was called “the Mexican American Dick Clark,” booked everyone from Los Tigres del Norte to Cheech Marin on his show.

Yet Canales will always be known for giving a teenage singer named Selena Quintanilla her first big break on television. Selena, the future Queen of Tejano Music, appeared in 1985 on “The Johnny Canales Show,” where he gently encouraged her to work on her Spanish.

Versions of Canales’ show ran until 2013, and they usually included him introducing performers with his catchphrase, “You got it, take it away!”

“Johnny wanted to break barriers and borders, and that’s what he did. By syndicating his show internationally, he rose above the ranks of local TV hosts,” documentarian Ramón Hernández said. “But it didn’t matter if you were a startup band or already famous; if Johnny thought you had talent, he would put you on his show.”

BARRY ROMO, 76, veterans advocate, anti-war activist. Romo was an eager young soldier when he enlisted in the U.S. Army and was sent to Vietnam in 1967. There he distinguished himself as a fighter, earning a Bronze Star. Yet the death of his nephew in combat fueled Romo’s disillusionment with war, and he became a fierce opponent of the conflict in Southeast Asia.

As a decorated veteran, Romo was an influential voice in the anti-war movement. In 1971, he helped organize a national protest in Washington, D.C., culminating with hundreds of veterans tossing their medals on the steps of the Capitol. In 1972, he went with singer Joan Baez on a humanitarian mission to Vietnam, where they survived 11 days of intense U.S. bombing.

For decades, Romo was a leader in Vietnam Veterans Against the War (VVAW), advocating for veterans’ benefits and the recognition of the effects of Agent Orange and in support of veterans of other wars.

“Barry lived with the war every day and every night; the fact that VVAW still exists today is a testament to him,” said Jeff Machota, a national staff member. “By keeping the group going, he helped vets suffering from PTSD or feeling suicidal. His work helped save lives.”

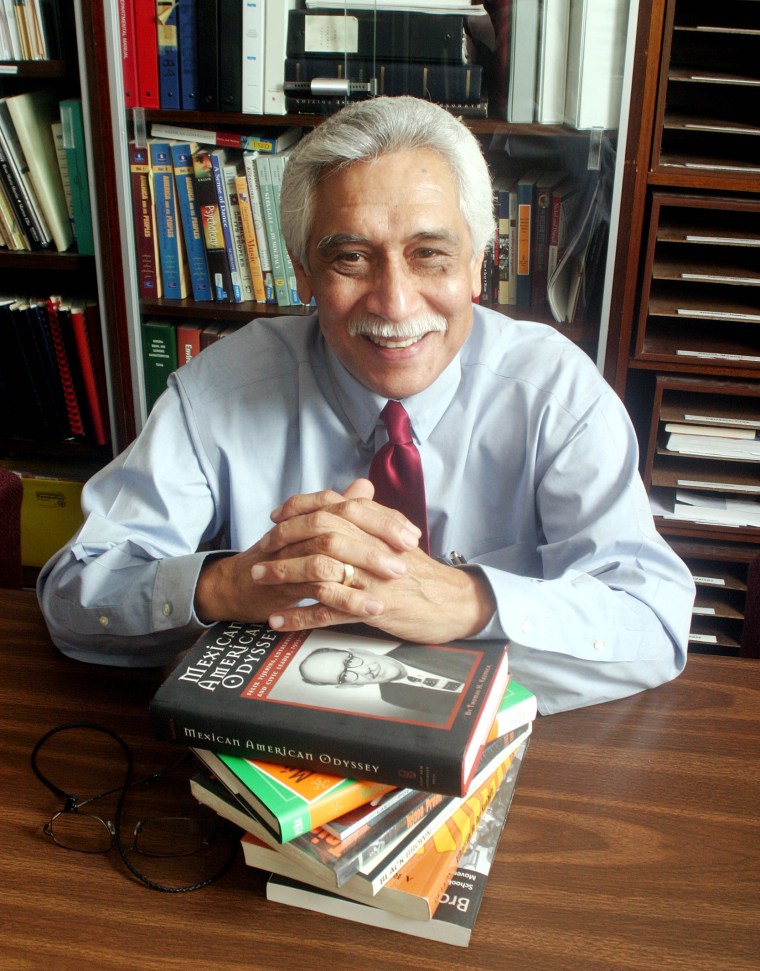

TATCHO MINDIOLA, 85, Mexican American studies pioneer. When Mindiola was in high school in the 1950s, a teacher discouraged his dreams of higher education by telling him, “Your people work behind the scenes.” Undeterred, Mindiola graduated from the University of Houston and then earned a Ph.D. from Brown University in 1978 — a time when few Latinos attended Ivy League schools.

Returning to the University of Houston, Mindiola started the Mexican American Studies program and built it into one of the premier programs of its kind. For 34 years, he mentored students who would become politicians, attorneys and journalists.

In 1972, Mindiola was among the founders of the National Association for Chicana and Chicano Studies. His work in Mexican American studies helped elevate the academic discipline, which traditionally hadn’t been viewed in the same light as other fields.

“He had that right combination of community, a sense of history, and he wanted to shine a light on the struggles of our gente [people],” Texas state Sen. Carol Alvarado said. “He knew that we had to learn about our past in order to be successful moving forward.”

EDUARDO XOL, 58, designer and TV personality. Xol spent seven seasons on ABC’s “Extreme Makeover: Home Edition” and was part of the team that earned the show Emmy Awards in 2005 and 2006.

Xol was passionate about arts and design. He was a musical child prodigy who appeared with the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra at age 10. Before he joined “Extreme Makeover” as a landscape designer, he starred in several Spanish-language telenovelas while producing music and videos in Latin America. He was the author of several books and was named one of “The 50 Most Beautiful” by People en Español in 2006.

“When he first came on the show, I heard a lot of people commenting on how good-looking he was,” said Ty Pennington, former host of “Extreme Makeover.” “But Eduardo was so much more than that; he was very sweet, very mellow and well-mannered.”

Pennington recalled that, when the show was working with Spanish-speaking families, Xol would put them at ease by speaking Spanish, as well. “He had a good way with people, with kids. He was a great team member; he had a very gentle soul.”

ELBA CABRERA, 90, arts and culture advocate. Coming from a family involved in public service, Cabrera didn’t believe in the stereotype of the “starving artist.” So she did something about it — and she became known as “La madrina de las artes” (the godmother of the arts), fostering and promoting arts and culture in New York City’s Puerto Rican community.

Cabrera was a community organizer, administrator and TV and radio host. She worked and served with the Association of Hispanic Arts, the Lehman Center for the Performing Arts in the Bronx, the Center for Media Arts and other nonprofit organizations. Dedicated to promoting Puerto Rican culture, she developed bonds with author Piri Thomas, poet Tato Laviera and New York City’s Puerto Rican Traveling Theater.

“Elba Cabrera gave a voice to people who often felt marginalized. She came from a precarious upbringing, being raised at the tail end of the Depression,” said Anibal Arocho, library manager at the Center for Puerto Rican Studies at Hunter College. “She was able to take the warmth she experienced in her life and exude it to everyone around her.”